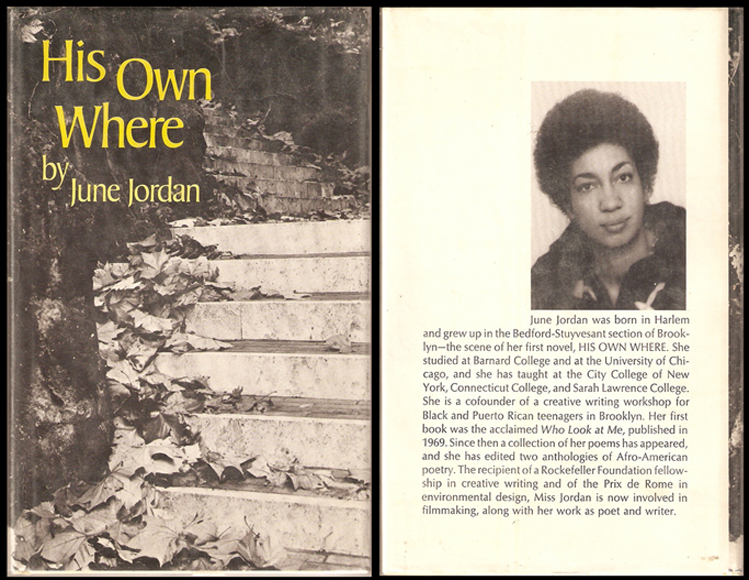

It can be difficult to tell your story if you use the language of your oppressors. That oppression can be overt or covert, and it can be centuries in the past or happening today, but the fact is that language affects how we perceive the world. Language affects how we can imagine a different world, too. June Jordan chose her words carefully and helped empower others to write their truths. [Insert June Jordan photo and credit: “Photo by Sara Miles”]

Photo by Sarah Miles

On July 9, 1936 two Jamaican immigrants living in Harlem, in Manhattan, New York, welcomed the birth of their daughter, June. They moved to Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, when Jordan was five years old. Life was not easy for the immigrants. In her biographical book from 1981, Civil Wars: Selected Essays, 1963-80, Jordan called her father “the first regular bully” in her life. She expanded upon her childhood in her 2000 book Soldier: A Poet's Childhood, which showed the complex feelings between child and parent when one is both a source of fear and love.

Jordan started writing at a young age, producing poems quickly. While her parents may not have fully grasped the power of poetry, they found a way to get her into Northfield School for Girls, a prep school located in Massachusetts. There her teachers encouraged her to write poetry but provided her with samples of only white authors’ work. During her teen years, her mother committed suicide.

She then attended Barnard College back in Manhattan, but felt frustrated by the lack of role models who looked like her or saw the world through similar eyes, so she left before graduation. She met her future husband, Michael Meyer, who was a student at the brother institution of Columbia. They married in 1955, and their interracial relationship was seen as unusual, even in NYC. In 1958 they had one child, Christopher David Meyer. Some of Jordan’s nonfiction work was published under the name “June Meyer,” though she did not use her husband’s surname elsewhere. By 1965, the couple divorced.

In 1966, after some film work with Frederick Wiseman and architect Buckminster Fuller, Jordan became interested in the living conditions of low-income African-American families. She was also a speechwriter for James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and for various city planning and youth social programs.

After her divorce she got a teaching position at the City College of New York in 1967. From 1968 to 1978, Jordan moved around, teaching at Yale University, Sarah Lawrence College, and Connecticut College. She wrote for the New York Shakespeare Festival, which produced more than just the Bard’s works. By the mid-1980s she was the head of the poetry center at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. By the end of that decade she moved to California to teach at the University of California at Berkeley. In 1991, she established Poetry for the People (P4P), a community group headquartered at the university. The group remains vital today, with the dual focus of higher education and outreach programs into the greater Bay Area.

Photo by tejason

By 1969, she published her first book, Who Look at Me, a project first pursued by Langston Hughes. The poems in this book used Black English or African-American vernacular, a choice Jordan made to help keep black cultures and communities alive by celebrating the words and rhythms they used. She continued to write for Black children in familiar language in four more books, both poetry and prose.

While in New York, Jordan worked with Black and Puerto Rican children during a workshop, encouraging them to write in the language they were most comfortable with. The result was the 1970 publication of THE VOICE of Children, a collection of 20 pieces laying out the realities of children in the ghettos. The same year, Jordan edited Soulscript: Afro-American, a poetry collection that contains works by the other poets who Jordan considered the most eloquent among Black artists.

Jordan wrote 25 volumes of fiction and nonfiction works of prose and poetry. Genre was not a limitation to her as she tackled issues of race, gender, and sexuality in plays, poems, libretti, essays, and children’s literature. Jordan received numerous awards for her work throughout the decades, including a Yaddo residency in 1979 and the Lila Wallace Reader’s Digest Writers Award in 1994. In 2017, the Center for Justice at Columbia University established the June Jordan Fellowship in her honor.

Was Jordan a feminist? Beyond the fact that some of her work was included in the anthology Homegirls: Anthology of Black Feminism in 1983, she often wrote about matters that fit into general feminist theory. She addressed sexuality and gender issues and defended homosexuality and bisexuality long before that was common and safe. Jordan even declared she was bisexual in some of her poems. Throughout her work, she addressed the reality of dual identities – common and individual – that each person struggles with.

Jordan developed breast cancer. On June 14, 2002, she passed on at the age of 65. Today a website has been established in her honor by The June M. Jordan Literary Estate Trust. You can check it to find events honoring her and inspired by her. You can listen to some of her powerfully read work here.