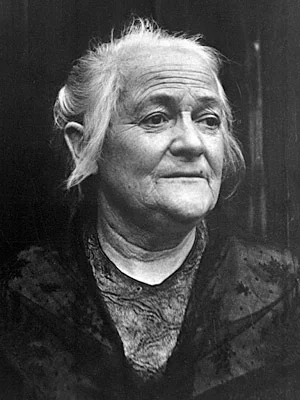

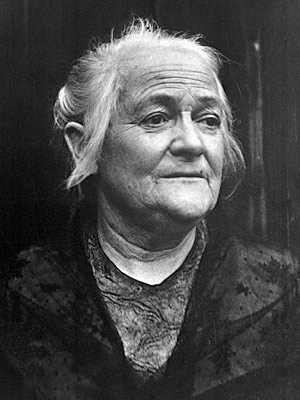

March 8th is International Women’s Day, a holiday honored by NOW every year. Such a day to recognize the role of women around the world may never have happened without the work of Clara Zetkin, one of the important Feminists and Marxists of Germany before World War II.

When Josephine Vitale Eißner and Gottfried Eißner brought their first daughter into the world in 1857, they named her Clara. Josephine was a highly educated woman from a middle class background, and Gottfried was a schoolmaster and church organist in Wiederau, Germany. Clara received a good education and trained to become a schoolteacher. During her education and her work she made friends with people in the labor and women’s movements. She first became a member of the German Women’s Association in 1875.

By 1878, she joined the Socialist Workers' Party, which in 1890 became the Social Democratic Party (SDP) that is still active in Germany today. Germany outlawed socialist parties in 1878, so it became dangerous to publicly associate with any such political or social group. By 1882, Clara moved to Zurich then Paris for several years, where she tutored factory workers so they might have a chance of improving their lives. She met and had two children with Ossip Zetkin, a Russian-Jewish activist, and took his surname, though it is unclear if they were legally married. When he died in 1889, Clara Zetkin retained the surname, even after she legally wed again in 1899.

After returning to Germany, Zetkin continued the fight for women’s suffrage and increased opportunity for women in the public sphere. However, she did not join existing feminism groups, because she was worried about their rejection of men as members. Zetkin believed that it was only by working to break down all rigid barriers between people that equality could be achieved. She is credited with creating the socio-democratic movement in Germany in the late 19th century. From 1891-1917, Zetkin edited the SDP’s women’s newspaper and was the first head of the SDP’s “Women’s Office” in 1907.

This image is in the public domain because its copyright has expired, and its author is anonymous.

Women were starting to demand recognition of their personhood. In New York in 1908, there was a “Women’s Day” that got the attention of some European women. During the International Women’s Conference of 1910, held right before the Socialist Second International Conference, either Zetkin or her sister feminist and socialist Luise Zietz suggested the establishment of an “International Women’s Day” (IWD). Zetkin helped organize the first IWD on March 19, 1911, in a handful of European countries. By 1917, after women gained the right to vote in Russia, the holiday was declared official for March 8th of every year. It quickly became part of the national calendars in socialist and communist countries. By 1975, the United Nations adopted the holiday.

Even though she was clearly raised in a middle class home, Zetkin was wary of “bourgeois feminism” and argued that only Socialism and later Communism could truly address the needs of working class women. One of their concerns was unnecessary war that only functioned to fraction the workers in favor of the elite. In 1915, she and sister activist Rosa Luxemburg created the first international women’s conference against World War I. By 1916, Zetkin co-founded the Spartacist League, a communist movement that helped generate public support that led to the German Revolution of 1918, and the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) in 1917.

While Zetkin and those in her organization did not get “a government based on local workers' councils” as they wanted, her affiliation with the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) brought her into political power as the representative of that party in the Reichstag from 1920-1933. In 1932, her seniority gave her the opportunity to give the opening address to the Reichstag. Known for her oratory skills, Zetkin used her 40-minute speech to call on all workers to unite and attacked Hitler and his party.

Photo by Daniel Weigelt

Zetkin did not give up on women’s rights. When Zetkin interviewed Vladmir Lenin in 1920, she was surprised that little was being done for working women and that he was critical of her focus on women. She seems to have been a bit overwhelmed by Lenin yet she still held her ground that women’s lives were important. Zetkin supported some of Luxemburg’s radical work on sexual liberation, which Lenin was not particularly fond of, as seen in the 1920 interview. Lenin’s death in 1924 led to a further stifling of the “woman question” in many organizations, yet Zetkin received two honors from the Russians for her work to promote communism, the Order of the Red Banner in 1927 and the Order of Lenin in 1932. [Insert Clara_Zetkin_Denkmal_Dresden image and credit “Photo by Daniel Weigelt”]

Back home in Germany, fallout from WWI was continuing to stir up social and political passions. When the Nazis took control in 1933, they promptly outlawed anything resembling communism or socialism. Zetkin fled to Russia, where she would die later that same year.

The majority of political and social systems are flawed when it comes to recognizing and promoting women’s rights. It can be difficult to be a powerful woman in any political party and to try to get something done for yourself and other women. Whether or not we agree with every stance that Zetkin took, she deserves credit for trying to create and keep a place for women in government and society, even when leaders of her own parties did not fully support her.